Water precautions advice post grommet insertion: a cross-sectional study of current Australian trend

Introduction

Insertion of grommet, or tympanostomy tube, is one of the most commonly performed procedures in otolaryngology (1). It is inserted across the tympanic membrane to ventilate the middle ear cavity, thus creating an open channel between the external environment and the middle ear system (1). Despite its small calibre, this open passage poses a theoretical risk of water penetration into the middle ear which can lead to complications including otorrhoea with associated discomfort and hearing impairment (2).

In Australia, approximately 9% of patients undergoing grommet insertion experience otorrhoea within 6 weeks post operatively (3). Although incidence of long-term otorrhoea in Australian patients remain yet to be defined, overseas research has shown up to 30–80% of patients experience at least one episode of otorrhoea while grommets are in situ (4). The two most commonly isolated pathogens from middle ear effusion have been Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae—two common nasopharyngeal pathogens associated with upper respiratory tract infections, thus pointing towards respiratory cause of grommet associated otorrhoea (5). However, other pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa—common external auditory canal pathogens—have been isolated, thus indicating possible contamination of middle ear by external canal pathogens through water exposure (6). Therefore, the traditional advice for post grommet insertion have often favoured restrictions to water activity (7).

Restrictions to water activity can take various forms including mechanical, chemical, and behavioural. There is no consensus on the best form of restriction, with clinical decisions often influenced by patient population and clinician’s previous experience (2). Mechanical restriction include ear plugs or cotton wool, chemical restrictions include topical antibiotic ear drops post water exposure, and behavioural restrictions include advising against head submersion under water or limiting water depth in diving (7). All of the above restrictions require patient co-operation, and may be associated with financial or psychological burden which could impair social development and introduction of essential water skills (2).

Consensus on water precautions have been difficult to achieve due to variable factors influencing the degree of water penetration through the grommet (8). One of these factors is the type of water that patients are exposed to, as less hydrostatic pressure is required in soapy water than distilled water due to reduced water surface tension (9). Other factors include depth of water exposure, grommet material and design, as well as patient factors such as time spent engaging in water activity and type of water encountered with varying degrees of bacterial load and aqueous contamination (1).

Clinical practice guidelines on tympanostomy tubes in children by American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAOHNS) in 2013 have recommended against use of routine water precautions post grommets (1). This recommendation was based on one randomised control trial (RCT) by Goldstein et al. and two systematic reviews of 11 observational studies which all reached similar conclusions (1). This guideline has been supported by the Cochrane systemic review in 2016 which also recommended against routine water precautions (2). This review was based on two RCTs by Goldstein et al., and Parker et al., both of which were also included in formation AAOHNS guidelines. It is interesting to note that Goldstein et al. found a statistically significant reduction in otorrhoea rates in children wearing ear plugs, with one episode of otorrhoea prevented during 2.8 years of ear plug use (4). However, authors still concluded against routine water precautions as the length of time taken to prevent one episode is outweighed by the inconvenience, anxiety and cost associated with water precautions, as well as the relatively low cost and uncomplicated treatment of most cases of otorrhoea (4).

Since the publication of the Cochrane review and AAOHNS guidelines, there have been further literature indicating no significant reduction in long term otorrhoea rates with routine water precautions (7,10-12). A recent Brazilian study by Miyake et al. (12) in 2019 found significant increase in the first post-operative month in otorrhoea rates in those with water precautions compared to those without, however, no significant difference between the two groups after the first month. Therefore, routine water precaution was recommended for the first post-operative month, but not thereafter.

Despite current guidelines and literature, clinical practices have been slow to adopt the findings (4). Previous surveys in the United States and the United Kingdom have shown 47% and 60.4% of clinicians respectively still recommend routine water precautions post grommet insertion (13,14). To our knowledge, there has been no previous counterpart survey performed in Australia. Through this study, our aim is to identify the current Australian trend of water precaution advice post grommet insertion, and to identify differences from the current guidelines and overseas counterpart surveys. We hope that this will aid in standardising patient care for such a common procedure to reduce patient confusion and ensure Australian practice is in line with current evidence based guidelines. The following article is presented in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Report of Observational studies in Epidemiology) reporting checklist (available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-22-13/rc).

Methods

A cross sectional survey of 9 questions (Appendix 1) were distributed via email by the Australian Society of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery (ASOHNS) to all qualified otolaryngologists and training registrars in Australia who are members of ASOHNS. Participation was voluntary and confidential with minimal identifying information including years of experience as otolaryngologist, and state of practice. Respondents were asked to select from a list of water precaution options relating to four main groups of water exposure: bathing, pool swimming, ocean swimming, and diving. Only one response was allowed per question. A free text box was included at the end of the survey for any additional comments from participants.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was granted ethics exemption by Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee, and informed consent has been waived from all participants. It has also been approved by the ASOHNS survey ethics committee prior to distribution of the survey.

Statistical analysis

Data was gathered on Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analysis was performed using SPSS v28.0.1.0. Further subgroup analysis was performed using Pearson’s Chi square, with significance set at P=0.05.

Results

Out of 498 surveys distributed to members of ASOHNS, there was a response rate of 34.9% with 174 responses; 6 responses with no answers for all questions were removed from analysis. There were no partially completed responses. Out of the 168 responses for analysis, participants composed of 165 consultant otolaryngologist and 3 registrars from variety of states and years of experiences, as shown in Table 1; 72.0% of participants had more than 10 years of experience as otolaryngologist. Three registrars still in training were classified as having less than 10 years of experience as otolaryngologist. Experience level of 10 years was chosen as it was seen as appropriate time for clinicians to become established in their practice and to gain experience regarding the water activity level of their local community, which could influence their water precaution advices. This 10-year timeframe also corresponded to publication of AAOHNS guideline in 2013 which could also influence the water precaution advice given by otolaryngologist (1). Due to small response number from states such as Northern Territory (NT) and Tasmania, one responses each respectively, responses were divided into Northern (NT and Queensland) and Southern states [New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia, Australian Capital Territory (ACT), and Tasmania] for further analysis.

Table 1

| Demographics | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Years of experience as otolaryngologist (n=168) | |

| <10 years | 47 (28.0) |

| >10 years | 121 (72.0) |

| State of practice (n=168) | |

| New South Wales | 56 (33.3) |

| Victoria | 36 (21.4) |

| Queensland | 36 (21.4) |

| Western Australia | 19 (11.3) |

| South Australia | 17 (10.1) |

| ACT | 2 (1.2) |

| NT | 1 (0.6) |

| Tasmania | 1 (0.6) |

ACT, Australian Capital Territory; NT, Northern Territory.

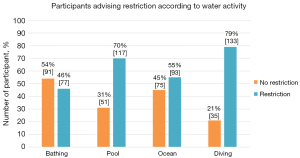

For bathing, 91 participants advised no restrictions, while 76 advised using ear plugs until grommet extrusion and 1 advised prophylactic antibiotic ear drops after bathing. For pool swimming, 51 advised no restrictions, 116 advised using appropriate barrier device, 1 advised no swimming until grommet extrusion, and 0 advised use of prophylactic antibiotic ear drops. This was similar to ocean swimming where 75 participants advised no restrictions, 92 advised using appropriate barrier device, 1 advised no swimming until grommet extrusion, and 0 advised use of prophylactic antibiotic ear drops. No swimming for ocean and pool swimming until grommet extrusion was advised by the same participant. Due to small number of responses in subgroups such as use of prophylactic antibiotics or complete avoidance of swimming while grommets in situ, comparison was made between ‘no restrictions’ and ‘restriction’ groups. ‘Restrictions’ included any chemical, mechanical, and/or behavioural restrictions advised post grommet insertion (Figure 1).

When divided according to experience level, there was no significant difference in water precaution advice given by otolaryngologist with greater than 10 years experience compared with those with less than 10 years experience for bathing (P=0.60), ocean swimming (P=0.30), pool swimming (P=0.51), and diving (P=0.93), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Water activity | <10 years | >10 years | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bathing | 20/47 (42.6%) | 57/121 (47.1%) | 0.60 |

| Ocean swimming | 23/47 (48.9%) | 70/121 (57.9%) | 0.30 |

| Pool swimming | 31/47 (66%) | 86/121 (71.1%) | 0.51 |

| Diving | 37/47 (79%) | 96/121 (79%) | 0.93 |

However, comparison between northern and southern states with regards to water precaution advice showed significant difference for pool swimming (P=0.01), with 86.5% in northern states advising restrictions compared to 64.9% in southern states. There was no significant difference found for bathing (P=0.70), ocean swimming (P=0.57), and diving (P=0.89) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Water activity | Northern states | Southern states | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bathing | 18/37 (48.6%) | 59/131 (45%) | 0.70 |

| Ocean swimming | 22/37 (59.5%) | 71/131 (54.2%) | 0.57 |

| Pool swimming | 32/37 (86.5%) | 85/131 (64.9%) | 0.01 |

| Diving | 29/37 (78%) | 104/131 (79%) | 0.89 |

Following on from significant difference found in advice regarding pool swimming, further subgroup analysis was performed to compare advice given by different experience groups according to their location of practice (Table 4). There was a significant difference in water restriction advice for pool swimming given by clinicians with <10 years of experience in northern states, compared with those in southern states, 91.7% and 57.1% respectively (P=0.03). There was no significant difference between northern and southern states (P=0.11) in >10 years of experience group.

Table 4

| Experience level | Northern | Southern | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 years | 11/12 (91.7%) | 20/35 (57.1%) | 0.03 |

| >10 years | 21/25 (84%) | 65/96 (67.7%) | 0.11 |

Thirty-three participants left further comments in the optional free text box, majority of which specified details of their water precaution regime after grommet insertion. These comments can be further accessed in Appendix 2.

Discussion

Water precaution advice post grommet insertion remains an area of controversy. This study has captured the current Australian practice for water precaution advice post grommet insertion, and aimed to identify any potential influencing factors.

Contrary to current guideline and literature advising against water restrictions, the results of this study have shown that many Australian clinicians continue to advise otherwise (1,2). There is a wide variability in practice with more than half of participants advising some form of water restriction when swimming in pool, ocean, and/or diving, 69.6%, 55.4%, and 79.2% respectively. This is further evident by free text box comments made by participants where a wide range of practice regimen can be appreciated. It is interesting to note that 45.8% of participants advised restrictions in bathing, as Ibrahim et al. (9) concluded that soapy water, most commonly encountered during bathing, requires the least amount of hydrostatic pressure to traverse the grommet to enter the middle ear cavity. However, our results indicate that clinicians are most comfortable to omit restrictions during bathing.

One of the main public health challenges faced by Australian otolaryngologists include provision of specialist health care to rural and regional areas, thus reducing the geographical discrepancies in health outcomes (15). Paediatric middle ear effusions and hearing loss is a major target for outreach programmes, however, insertion of grommets in these rural settings are often avoided due multiple concerns including poor adherence to water precautions and potential otorrhoea where there is paucity of medical follow-up. With relaxation of water precaution advice as suggested by current guidelines, grommet insertion may become available as a treatment option for these regional communities, thus progressing towards healthy equity and one step closer to ‘closing the gap’.

There may be multiple factors contributing to the deviation of current Australian practice away from clinical guidelines. This includes clinician’s anecdotal experience and knowledge of local geographical factors that impact otorrhoea rates, such as locally available bodies of water for water activity and their bacterial load, and water activity level of their patient population. Certain pathogens, such as Pseudomonas, thrive in warm water and can be present in high concentrations in still-water dams or in heated pools where children often swim (16). As northern states include tropical areas with higher water temperatures, as well as possible longer duration of water activity due to warmer weathers, clinicians may incline towards conservative restrictions during water exposure (17). This could account for the significantly higher proportion of water precaution advice for pool swimming given by northern clinicians compared to southern counterparts, 86.5% and 64.9% respectively. Although Western Australia encompasses a large area with water conditions similar to both northern and southern states, it was included as southern state for our analysis as majority of Western Australian population is based in metropolitan cities in southern parts of the state with water conditions comparable with other southern states of Australia (18).

Another factor influencing Australian practice to vary from guidelines may be the absence of local Australian data in formation of current AAOHNS guidelines. Advice from current guidelines based on overseas population may be less relevant in Australia as regional pathogens can vary widely (19). AAOHNS guidelines and Cochrane review were both based on RCTs by Goldstein et al. and Parker et al. which were based in Pittsburg and Portsmouth USA respectively. These are both cities with cold winter months which would impact water activities to be limited during those seasons. Especially in the study by Goldstein et al., majority of the study population is under 3 years old who are likely to have limited head submersion during water activity, therefore outcome of this study may not be relevant to the local Australian population.

Interestingly, a Brazilian RCT by Miyake et al. published in 2019 after the above guidelines also recommended against long term water precaution post grommet insertion (12). This result may be more relevant in local context as water activity levels as well as water temperatures in Brazil may be more comparable to northern Australia. However, further information regarding types of water bodies including dams, lakes, ocean is required to determine their relevance in influencing water precaution advices.

Similar surveys have been performed in the United States by Poss et al. in 2008, United Kingdom by Basu et al. and Ridgeon et al. in 2007 and 2015 respectively, and in New Zealand by Davison in 1993 (13,14,20,21). Similar to our findings, all of the studies found wide variation in practice with no consensus on water precaution advice post grommets, with majority advising some form of restriction. Even after the first AAOHNS guidelines was published in 2013, Ridgeon et al. concluded in 2015 that water precaution advice continues to be varied and not in agreement with the guidelines or evidence on which guidelines are based (11).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the current Australian practice for water precaution advice post grommet insertion. Through our distribution of the survey, otolaryngologists of a range of experience levels from various locations around Australia were able to be reached. The main limitation of this survey lies in the multiple choice style questions which limit possible responses and lack flexibility that is often found in real practice. However, the questions were designed this way to encourage participation, and an open text box was included to enable any further comments. On retrospect, question regarding ‘diving’ can have wide interpretations between participants and this could lead to inconsistencies in answer of this question.

Another limitation is the relatively small sample numbers which act as a barrier to identifying any local trends in practice, especially in smaller states and territories. This is further compounded by paucity of long term data on Australian incidence of otorrhoea related to grommet insertion. Further local research to identify the Australian incidence of grommet related otorrhoea rates, as well as a larger study of water precaution advice with information on rurality of a clinician’s practice would aid in identifying further regional influences on water precaution advice that would need to be accounted for when developing a standardised practice guideline. This in turn would help to reduce patient confusion and potentially remodel the range of outreach otolaryngological service that is provided to target the health discrepancies present among the Australian regional and remote communities.

Conclusions

Traditional water precaution advice post grommet insertions has been repeatedly challenged by current guidelines and various studies in the literature. However, as shown by this study, water precautions post grommets continue to be routinely advised by many Australian otolaryngologists. There is significant difference found in advice regarding pool swimming with clinicians in northern states advising more water precautions than their southern state counterparts. The wide variability in practice found in this study indicate the need for an established local guideline to standardise practice and ensure patients receive evidence-based advice. It is hoped that this study will provide local information to Australian otolaryngologists to aid in clinical judgement when providing water precaution advice post grommet insertions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Jai Lembryk for his technical support for data synthesis and analysis.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-22-13/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-22-13/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-22-13/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-22-13/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was granted ethics exemption by Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee, and has also been approved by the ASOHNS survey ethics committee prior to distribution of the survey. Informed consent has been waived from all participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;149:S1-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moualed D, Masterson L, Kumar S, et al. Water precautions for prevention of infection in children with ventilation tubes (grommets). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;CD010375. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang LC, Giddings CE, Phyland D. Predictors of postoperative complications in paediatric patients receiving grommets - A retrospective analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2021;142:110601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldstein NA, Mandel EM, Kurs-Lasky M, et al. Water precautions and tympanostomy tubes: a randomized, controlled trial. Laryngoscope 2005;115:324-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dohar J. Microbiology of otorrhea in children with tympanostomy tubes: implications for therapy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2003;67:1317-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Dongen TM, Venekamp RP, Wensing AM, et al. Acute otorrhea in children with tympanostomy tubes: prevalence of bacteria and viruses in the post-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34:355-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salata JA, Derkay CS. Water precautions in children with tympanostomy tubes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:276-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carbonell R, Ruíz-García V. Ventilation tubes after surgery for otitis media with effusion or acute otitis media and swimming. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2002;66:281-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim Y, Fram P, Hughes G, et al. Water penetration of grommets: an in vitro study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017;274:3613-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Subtil J, Jardim A, Peralta Santos A, et al. Water protection after tympanostomy (Shepard) tubes does not decrease otorrhea incidence - retrospective cohort study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2018;84:500-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Subtil J, Jardim A, Araujo J, et al. Effect of Water Precautions on Otorrhea Incidence after Pediatric Tympanostomy Tube: Randomized Controlled Trial Evidence. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;161:514-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miyake MM, Tateno DA, Cançado NA, et al. Water protection in patients with tympanostomy tubes in tympanic membrane: a randomized clinical trial. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2019;17:eAO4423. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poss JM, Boseley ME, Crawford JV. Pacific Northwest Survey. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2008;134:133. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ridgeon E, Lawrence R, Daniel M. Water precautions following ventilation tube insertion: what information are patients given? Our Experience. Clin Otolaryngol 2016;41:412-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- RACS. Rural Health Equity - Strategic Action Plan. 1st ed. RACS, 2020. Available online: https://www.surgeons.org/-/media/Project/RACS/surgeons-org/files/interest-groups-sections/Rural-Surgery/RPT-Rural-Health-Equity-Public-FINAL.pdf?rev=1709767dffbd48cda7dbfa3c053c6b58&hash=717809CD51D32CE7F4C9

- Mena KD, Gerba CP. Risk assessment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in water. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 2009;201:71-115. [PubMed]

- Guzman Herrador BR, de Blasio BF, MacDonald E, et al. Analytical studies assessing the association between extreme precipitation or temperature and drinking water-related waterborne infections: a review. Environ Health 2015;14:29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2016-17. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/3218.0Main+Features12016-17

- Wilson ME. Geography of infectious diseases. Infectious Diseases 2010;1055-64. [Crossref]

- Basu S, Georgalas C, Sen P, et al. Water precautions and ear surgery: evidence and practice in the UK. J Laryngol Otol 2007;121:9-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davison MJ, Fields MJ. Ventilation tubes, swimming and otorrhoea: a New Zealand perspective. N Z Med J 1993;106:201-3. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: You WS, Cooper L, Cronin M. Water precautions advice post grommet insertion: a cross-sectional study of current Australian trend. Aust J Otolaryngol 2022;5:22.