Variation in management of post-tonsillectomy haemorrhage: a survey of Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Consultants and Registrars

Introduction

Tonsillectomy is a commonly performed elective procedure in Australia with 750 tonsillectomies performed for every 100,000 children aged 17 years or below (1). There is a documented rate of un-planned admissions related to this procedure. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported a rate of 39 readmissions per 1,000 separations for Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy (2). Readmissions following tonsillectomy can be due to a number of factors including; dehydration, pain, nausea/vomiting, sleep disturbance and bleeding/haemorrhage (3). Post tonsillectomy haemorrhage (PTH) can be divided into primary—occurring within 24 hours of the procedure and secondary—occurring more than 24 hours after the procedure, typically between days five to ten postoperatively (4-6).

Peri- and post-operative management of the patient undergoing tonsillectomy has been well outlined in the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery foundation guidelines (5). However, the management of PTH lacks significant evidence. Patient reported symptoms generally range from an episode of blood-tinged saliva to persistent active bleeding. The examination of the tonsil fossa is the critical factor in guiding further management. Approximately 65% of patients will present with a positive oropharyngeal examination classified as: clot in tonsillar fossa (49%), ooze (22%), clot and ooze (6%) or active bleeding (23%) (6). In cases where there is persistent active bleeding, there is wide consensus that these patients require operative management (3,7). A number of surveys of United States Otolaryngologists demonstrated consistency, with more than 80% recommending theatre for the persistent active bleeding category of patients (3,7). For those that present with a history of recent but not active bleeding on examination there are a range of specific management options.

Clinical decision-making is based on multiple factors including age, severity of bleeding, as well as examination findings of a clot, or a slow ooze of blood in the oropharynx. Factors contributing to this clinical dilemma are the variety of treatments available as well as the large numbers of patients that would be required in a clinical trial to provide sufficient power for statistical analysis (8). Interventions for low risk patients in the current literature include; IV fluids, steroids, antibiotics, tranexamic acid (TXA), hydrogen peroxide gargles, haemostatic agents (e.g., Floseal), clot suctioning, topical adrenaline, desmopressin (DDAVP) and silver nitrate cautery (3,7,9-12).

Further complicating current management are the differences between PTH in various age demographics. Sarny et al. (2011) showed that adults had a three times higher rate of PTH compared to school-aged children (13). However, school aged children were at higher risk of severe haemorrhage post-tonsillectomy compared to adults and younger children (13). In contrast, children aged less than six years old with a normal oropharyngeal exam were significantly less likely to require any medical intervention (6).

The aim of our study is to survey current Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery (ASOHNS) Consultants and Registrars to assess the current treatment implemented in various hospitals around Australia and compare these results with the current literature. ASOHNS is the representative organization for Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgeons in Australia. Our survey presented multiple clinical presentations for PTH for those aged less than and more than six years old. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-21-49/rc).

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2013). The study was approved as a Quality Improvement Project by the Southern Adelaide Local Health Network HREC who deemed specific ethics review was not required. A preliminary search of the literature as well as local guidelines and protocols was conducted in April 2020. This search was used to identify a list of common investigation and management options for PTH (Appendix 1). Articles were identified through MEDLINE (PubMed) using the following search strategy: tonsillectomy[tw] AND (haemorrhage[tw] OR hemorrhage[tw] OR bleed[tw] OR bleeding[tw]). The search, ‘post tonsillectomy haemorrhage protocol’ was used to identify publicly available local guidelines through the Grey literature (Google). A cross-sectional survey was subsequently developed and presented to ASOHNS for review. The survey was distributed directly by ASOHNS to each member’s email address from a database held by ASOHNS. Informed consent was obtained by each of the participants. The survey was initially distributed in February 2021 using the online platform, SurveyMonkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com). The survey was re-distributed two weeks after initial distribution and open for a total of one month before closure to maximize member response. All responses were anonymous with participation and completion of the survey done voluntarily. Completion of the entire survey was not required for responses to be included.

The survey consisted of nine demographic questions including age, state they were practicing in, type of practice, level of training and frequency of PTH management. Three clinical scenarios for patients presenting to hospital with PTH for those aged less than and those aged more than six years old were presented to participants. The age groups selected were based on two previous studies of PTH that identified patients who were less than six years old were both less likely to experience severe haemorrhage and less likely to require intervention (6,13). Our clinical scenarios covered three common presentations for PTH that reflected scenarios surveyed in a similar study of American Paediatric Otolaryngologists (7). Management options for PTH that were identified in the preliminary search were provided for selection.

Statistical analysis

In regards to statistical analysis, categorical data was analysed with the Chi square test and Fisher’s exact test for n × m and 2×2 contingency tables respectively. Logistic regression was performed to assess the differences within multicategorical independent variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27 (IBM, USA).

Results

Demographic data

A total of 163 out of the 565 members responded to our survey (giving us a 29% response rate), 127 and 36 of the 565 members responded on initial and subsequent distribution respectively. Demographic data is outlined in Table 1. Most respondents were from New South Wales (31.9%), Victoria (24.5%) and Queensland (19.6%). Only a small proportion practiced primarily in small rural/regional areas (4%).

Table 1

| Demographics | Participants, % [n] |

|---|---|

| State of practice | |

| Australian Capital Territory | 0.6 [1] |

| New South Wales | 31.9 [52] |

| Northern Territory | 1.2 [2] |

| Queensland | 19.6 [32] |

| South Australia | 9.8 [16] |

| Tasmania | 1.8 [3] |

| Victoria | 24.5 [40] |

| Western Australia | 10.4 [17] |

| Primary practice location | |

| Capital/Major city | 81.6 [133] |

| Large regional city | 14.1 [23] |

| Small rural/regional area | 4.3 [7] |

| Primary practice type | |

| Public | 24.5 [40] |

| Private | 23.9 [39] |

| Both | 51.5 [84] |

| Level of training | |

| Consultant | 78.5 [128] |

| Registrar | 21.5 [35] |

| Years since obtaining FRACS | |

| 0–10 years | 33.3 [43] |

| 11–25 years | 43.4 [56] |

| >25 years | 23.3 [30] |

| Completed paediatric fellowship | |

| Yes | 15.5 [20] |

| No | 84.5 [109] |

ASOHNS, Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery.

A summary of the responses for the following three clinical scenarios is highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2

| Treatment option | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than six years old | More than six years old | Less than six years old | More than six years old | Less than six years old | More than six years old | |||

| CBE/FBE | 97 (68.3) | 93 (65.5) | 108 (80.0) | 103 (76.3) | 119 (89.5) | 115 (86.5) | ||

| Coagulation studies | 52 (36.6) | 49 (34.5) | 65 (48.2) | 60 (44.4) | 85 (63.9) | 83 (62.4) | ||

| Group and Hold | 72 (50.7) | 65 (45.8) | 90 (66.7) | 80 (59.3) | 117 (88.0) | 114 (85.7) | ||

| IV access | 103 (72.5) | 95 (66.9) | 127 (94.1) | 122 (90.4) | 130 (97.7) | 128 (96.2) | ||

| IV fluids | 52 (36.6) | 45 (31.7) | 78 (57.8) | 73 (54.1) | 120 (90.2) | 116 (87.2) | ||

| Steroids | 10 (7.0) | 10 (7.0) | 10 (7.4) | 11 (8.2) | 17 (12.8) | 17 (12.8) | ||

| Antibiotics | 58 (40.9) | 56 (39.4) | 70 (51.9) | 68 (50.4) | 74 (55.6) | 73 (54.9) | ||

| Tranexamic acid | 52 (36.6) | 62 (43.7) | 76 (56.3) | 90 (66.7) | 93 (69.9) | 106 (79.7) | ||

| Hydrogen peroxide gargles | 18 (12.7) | 49 (34.5) | 30 (22.2) | 85 (63.0) | 24 (18.1) | 50 (37.6) | ||

| Haemostatic agent (e.g., Floseal) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 4 (3.0) | ||

| Silver nitrate cautery | 1 (0.7) | 5 (3.5) | 1 (0.7) | 13 (9.6) | 3 (2.26) | 32 (24.1) | ||

| Topical adrenaline gauze | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 9 (6.8) | 29 (21.8) | ||

| DDAVP | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Take the patient to the operating theatre | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 13 (9.6) | 4 (3.0) | 119 (89.5) | 96 (72.2) | ||

| Suction clot | N/A | N/A | 7 (5.2) | 27 (20.0) | N/A | N/A | ||

Data is expressed as numbers (percentages). CBE, complete blood examination; FBE, full blood examination; DDAVP, desmopressin.

(I) Scenario one: a patient presents to hospital several days following tonsillectomy with a self-reported episode of blood they had coughed up with no signs of clots or bleeding on examination.

A total of 142 respondents completed this scenario. The majority of respondents would take bloods on admission including complete blood examination (CBE) (67%) and Group and Hold (48%). Obtaining IV access was also common (70%) without necessarily giving intravenous fluids (34%). Less commonly selected options included; coagulation studies (36%), antibiotics (40%) and TXA (40%). Hydrogen peroxide gargles were selected less frequently in those less than compared to more than six years old (13% vs. 35%). Respondents infrequently selected any other treatment options. Two respondents selected to take the patient less than six years old to theatre for further management in this scenario whereas none of the respondents selected this option for the patient more than six years old.

(II) Scenario two: a patient presents to hospital several days following tonsillectomy with a self-reported episode of bleeding with a clot in their tonsillar fossa on examination.

A total of 135 respondents completed this scenario. The majority of respondents would take bloods on admission including CBE (78%) and Group and Hold (63%), obtain IV access (92%) and initiate intravenous fluids (56%). Within this scenario, for all age groups the majority would also treat with TXA (62%) and antibiotics (51%). Use of hydrogen peroxide gargles in patients more than six years old was also a common option (63%). Coagulation studies were less commonly selected (46%). Five percent and twenty percent of responders would suction the clot from the tonsillar fossa in this scenario for those aged less and more than six years old respectively. More respondents would take a patient less than six years old (10%) compared to more than six years old (3%) to theatre in this scenario.

(III) Scenario three: a patient presents to hospital several days following tonsillectomy with an episode of bleeding. On examination, there is no clot present but there is ongoing bleeding from the tonsillar fossae.

A total of 133 respondents completed this scenario. The majority of respondents would take bloods on admission including CBE (88%), coagulation studies (63%) and group and hold (87%). Obtaining intravenous access (97%) and initiating intravenous fluids (89%) was also common. In those aged more than compared to less than six years old respectively, respondents also selected; hydrogen peroxide gargles (38% vs. 18%), silver nitrate cautery (24% vs. 2%) and topical adrenaline gauze (22% vs. 7%). The majority of respondents would take both age groups to theatre for definitive management (81%).

Length of admission

When asked about decisions to discharge patients from the emergency department most respondents selected the option to admit for observation. This was most evident in scenario three where only 1 of the 133 respondents elected to discharge patients from both age groups from the emergency department. In scenario two, 96% and 99% would admit those aged more than and less than six years old respectively. In scenario one, however, we found that around one third of members (33%) would discharge patients over the age of six home from ED, whereas significantly less would do so for those aged less than six years old (13%). In terms of length of admission, in general for scenario one respondents would admit for <24 hours but >24 hours for those in scenario two and three, see Table 3 below.

Table 3

| Scenario | Less than six years old | More than six years old | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admit for observation | Less than 24 hours | Admit for observation | Less than 24 hours | ||

| Scenario 1 | 123 (86.6) | 90 (63.4) | 95 (66.9) | 109 (76.8) | |

| Scenario 2 | 134 (99.3) | 54 (40.0) | 130 (96.3) | 59 (43.7) | |

| Scenario 3 | 132 (99.3) | 34 (25.6) | 132 (99.3) | 40 (30.1) | |

Data is expressed as numbers (percentages).

The two factors impacting on the treating clinician’s management for both age groups were the distance the patient lives from hospital and availability of social supports. We identified that more than 90% of respondents’ management would be influenced by these factors, more so for those aged less than six years old.

Available data was then sub grouped by

- Level of training: Registrar vs. Consultant (with or without paediatric fellowship).

- State of practice: ACT, NSW, NT, QLD, SA, Tasmania, Victoria, WA.

- Primary practice location: Capital/Major city, Large regional city, Small rural/regional area.

- Primary practice type: Public, Private, both.

Level of training

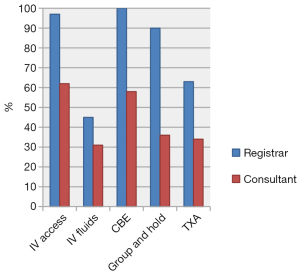

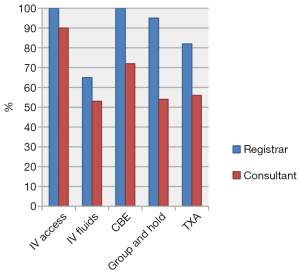

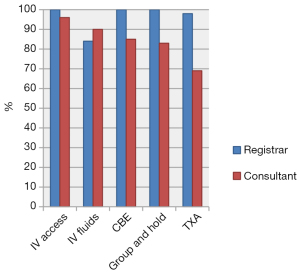

A few key differences were noted, especially in scenario one and two between Registrars and Consultants, see Figures 1-3. In scenario one Registrars were more likely than Consultants to obtain IV access (97% vs. 62%, P≤0.001), give IV fluids (45% vs. 31%, P=0.029), take a CBE (100% vs. 58%, P<0.001), Group and Hold (90% vs. 37%, P<0.001) as well as give TXA (63% vs. 34%, P<0.001). Similar findings were seen in scenario two between Registrars and Consultants for IV access (100% vs. 90%, P=0.004), IV fluids (65% vs. 53%, P=0.072), CBE (100% vs. 72%, P<0.001), Group and Hold (95% vs. 54%, P<0.001) and TXA (82% vs. 56%, P<0.001). In contrast, Consultants were more likely than Registrars to prescribe antibiotics (59% vs. 43%, P=0.026) in scenario three, to suction tonsillar fossa clots (14% vs. 7%, P=0.084) in scenario two and discharge patients from the emergency department (28% vs. 6%, P<0.001) in scenario one. There was no clear consensus regarding length of observation. No significant differences were found between consultants that had undergone paediatric fellowships from those who had not.

By state

There were a small number of respondents from the ACT, NT and Tasmania with one, two and three responses respectively. ASOHNS respondents from Queensland were less likely than the average of other states to obtain bloods in scenario one (CBE: 42% vs. 74%; P<0.001, Coagulation studies: 15% vs. 41%; P=0.002, Group and Hold: 32% vs. 53%) and scenario two (CBE: 65% vs. 82%; P=0.005, Coagulation studies: 33% vs. 50%; P=0.022, Group and Hold: 52% vs. 66%; P=0.040). We also found that respondents from Queensland and Western Australia were more likely to use TXA compared to the other states (QLD: 81%, WA: 73%, Other: 49%; P<0.001).

By location

Eighty-two percent of respondents worked in major cities with only 14% and 4% in large regional cities and small regional areas respectively. Due to the small numbers in the latter groups, we were unable to accurately assess for any differences.

By practice type (private/public)

Respondents working in the private sector were more likely to prescribe antibiotics than those who worked in the public sector (63% vs. 39%, P<0.001). For scenarios one and two however, respondents working in the public sector were more likely than those who worked in the private sector to take bloods (CBE: 89% vs. 58%; P<0.001, Coagulation studies: 51% vs. 30%; P<0.001 Group and Hold: 85% vs. 42%; P<0.001), obtain IV access (92% vs. 68%; P<0.001) and utilize TXA (72% vs. 36%; P<0.001).

Discussion

Our study has identified some key aspects and variability in the management of PTH across Australia. There appears to be a common increase in the use of TXA across Australia but there was also variability between subgroups seen in decisions to prescribe antibiotics, suctioning of tonsillar fossa clots and use of TXA. Overall, common treatment options selected by the majority of respondents for any patient presenting with a post-tonsillectomy bleed included; IV access and bloods, IV fluids, antibiotics, hydrogen peroxide gargles and TXA. Across Australia multiple publicly available local protocols and guidelines exist for management of PTH (14-16). The majority of which would have been used and/or created by the subjects enrolled in this study. Routine bloods (CBE and G+H), IV fluids and hydrogen peroxide gargles are recommended in most Australian guidelines (14,15).

Following data collection, we contacted the Queensland Children’s Hospital Otolaryngology department for access to their PTH management protocol (G. Krishnan, personal communication, October 26, 2021). We found that their protocol recommends intravenous TXA for all patients presenting with a fresh PTH. Higher use of TXA by respondents from Queensland in our study is consistent with this protocol. Similarly, increased utilisation of TXA in the Western Australian cohort was also reflected in the Perth Children’s Hospital protocol (15) . Since its introduction in the 1960’s, a growing body of literature has supported the use of TXA to assist in the management of major bleeding and PTH (17,18). Two recent randomized controlled trials include WOMAN (2017) and CRASH-2 (2010) that compared TXA versus placebo in post-partum haemorrhage and civilian trauma respectively. Both trials showed a significant reduction in the risk of death due to bleeding (19,20). The increased awareness of TXA as an adjunct to the management of severe bleeding over the past decade may explain why registrars and doctors working in public tertiary hospitals may be more likely to utilize TXA than those working privately with less exposure to trauma with life threatening bleeding.

Our findings are in agreement with previous international studies that have shown variability in the bedside management implemented for patients who present without active bleeding (3). In patients who present with active bleeding, we found that 81% of respondents would proceed to theatre for definitive management. This is consistent with a recent survey that found that 82% of American Society of Paediatric Otolaryngologists would proceed to theatre when presented with the same scenario (7). In terms of other bedside treatments, our results did not identify topical adrenaline/haemostatic agents (e.g., Floseal) or DDAVP as commonly utilised options. A study by Binnetoglu et al. assessed the results of intraoperative topical Floseal without cautery for management of secondary PTH where there was a diffuse ooze. This retrospective study identified achievement of haemostasis in 41 out of 42 patients who were treated in this manner (12). The PTH protocol utilized at the Perth Children’s Hospital also suggests that DDAVP can be considered for these patients (15). Our study has identified that Floseal and DDAVP may be underutilized in PTH situations.

The main differences between those aged more than and those less than six years old were generally related to use of hydrogen peroxide gargles, silver nitrate cautery, and topical adrenaline as well as suctioning of tonsillar fossa clots. We speculate that these findings are related to the child’s ability to cooperate with such interventions. We also found that respondents were also more likely to proceed to theatre for definitive management and admit patients who were less than six years old. Despite previous studies suggesting that these patients were less likely to require intervention (6,13), their lower circulating blood volume and potential for haemodynamic instability likely explain our survey findings.

Surveying ASOHNS Consultants and Registrars has allowed us to gain insight into the general management of PTH across Australia. The survey questions were useful in depicting the common presentations for this condition. There were however some limitations to our study that impact on the generalizability of our results. The clinical scenarios were simplified to include a limited number of factors as inclusion of greater than ten factors would have exponentially increased the number of questions and may have impacted on response rates. The factors we could have included were hemodynamic status of the patient, clinical progression during admission, quantitative measure of bleeding, patient specific factors and their ability to tolerate bedside treatment. On top of this, as we often find in clinical practice, in patients who present with clots or active bleeding, we often utilize a stepwise approach to each bedside treatment instead of implementing them all at once. Only after which will the decision be made if the patient requires management in the operating theatre. Although we did achieve a modest response rate from our survey, there does also exist the potential for response bias from the cohort that did not respond to our survey. Our survey also didn’t differentiate between registrars of varying experience.

Our findings in general reflect the guidance of local protocols but in doing so also highlights the differences in management of PTH between states and also between our public and private hospital systems. The findings from our study can be used in future studies to develop statewide or national guidelines on the management of PTH. Ongoing research is required into the effectiveness of the less commonly utilized non-surgical management options to assess if their use can help to reduce the need to return to theatre for definitive management.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery for help with distribution of the survey.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-21-49/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-21-49/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-21-49/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://www.theajo.com/article/view/10.21037/ajo-21-49/coif). EO is Member of National Board of Training, Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, RACS, Vice President of the Australian and New Zealand Head and Neck Cancer Society, Executive board member as SA representative for the Laryngology Society of Australasia and he is a co-inventor of PCT patent application (No. PCT/AU2021/050723, 2021) about StaVarSel method. EO received Medtronic honoraria for webinars on BiZact tonsillectomy. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2013). The study was approved as a Quality Improvement Project by the Southern Adelaide Local Health Network HREC who deemed specific ethics review was not required. Informed consent was obtained by each of the participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ear, nose and throat surgery for children and young people. The Fourth Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2021:177.

- Admitted patient care 2017-18 Australian hospital statistics. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2019.

- Clark CM, Schubart JR, Carr MM. Trends in the management of secondary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2018;108:196-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Attner P, Haraldsson PO, Hemlin C, et al. A 4-year consecutive study of post-tonsillectomy haemorrhage. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2009;71:273-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell RB, Archer SM, Ishman SL, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Tonsillectomy in Children (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;160:S1-S42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arora R, Saraiya S, Niu X, et al. Post tonsillectomy hemorrhage: who needs intervention? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2015;79:165-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El Rassi E, de Alarcon A, Lam D. Practice patterns in the management of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage: An American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology survey. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2017;102:108-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whelan RL, Shaffer A, Anderson ME, et al. Reducing rates of operative intervention for pediatric post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage. Laryngoscope 2018;128:1958-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pai I, Lo S, Brown S, et al. Does hydrogen peroxide mouthwash improve the outcome of secondary post-tonsillectomy bleed? A 10-year review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;133:202-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harounian JA, Schaefer E, Schubart J, et al. Pediatric Posttonsillectomy Hemorrhage: Demographic and Geographic Variation in Health Care Costs in the United States. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;155:289-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdelhamid AO, Sobhy TS, El-Mehairy HM, et al. Role of antibiotics in post-tonsillectomy morbidities; A systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2019;118:192-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Binnetoglu A, Demir B, Yumusakhuylu AC, et al. Use of a Gelatin-Thrombin Hemostatic Matrix for Secondary Bleeding After Pediatric Tonsillectomy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;142:954-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sarny S, Ossimitz G, Habermann W, et al. Hemorrhage following tonsil surgery: a multicenter prospective study. Laryngoscope 2011;121:2553-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clinical Practice Guideline. Post Tonsillectomy Bleeding. The Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital. 2018. [cited 2022 12 April]. Available online: https://eyeandear.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Post-Tonsillectomy-Bleeding-Clinical-Practice-Guideline.pdf

- Perth Children’s Hospital: Government of Western Australia Child and Adolescent Health Service. Post tonsillectomy haemorrhage. 2021. [cited 2022 12 April]. Available online: https://pch.health.wa.gov.au/For-health-professionals/Emergency-Department-Guidelines/Post-tonsillectomy-haemorrhage

- The Children’s Hospital at Westmead. Secondary Haemmorage Post-Tonsillectomy and Adenoid Surgery management - ED – CHW. 2020. [cited 2022 14 April]. Available online: https://www.schn.health.nsw.gov.au/_policies/pdf/2020-158.pdf

- Tengborn L, Blombäck M, Berntorp E. Tranexamic acid--an old drug still going strong and making a revival. Thromb Res 2015;135:231-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith AL, Cornwall HL, Zhen E, et al. The therapeutic use of tranexamic acid reduces reintervention in paediatric secondary post-tonsillectomy bleeding. Aust J Otolaryngol 2020;3:10. [Crossref]

- WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389:2105-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- CRASH-2 trial collaborators; Shakur H, Roberts I, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:23-32.

Cite this article as: Lee TJ, Wood J, Ooi EH. Variation in management of post-tonsillectomy haemorrhage: a survey of Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Consultants and Registrars. Aust J Otolaryngol 2022;5:21.