Support group preferences for patients with head and neck cancer: cross-sectional survey

Introduction

Cancers arising from the head and neck represents the seventh most common cancer site in Australia (1), accounting for over 700,000 (over 5%) new cancer diagnoses worldwide and an estimated 450,000 (4.8%) deaths each year (2). The demographics and prognosis of patients with head and neck cancer are diverse and continually changing. In contrast to tobacco-related mucosal cancer, human papilloma virus (HPV)-related oropharyngeal cancers are common in younger males (3). HPV associated tumours have a much more favourable prognosis than smoking associated mucosal cancers (4). Several new treatments are emerging, such as immunotherapy, which are prolonging the lives of many patients with head and neck cancer. Improved survival means a larger cohort of patients are living with the long-term effects of the cancer and its treatment on their quality of life (QOL) (5). These patients live with the physical and emotional consequences of treatment, and have a complex and evolving psychological and physical state that is unlike other cancer diagnoses (6). Education and emotional support are required by many individuals to cope with these challenges.

Cancer support groups have predominantly been implemented and studied in other diagnoses, particularly breast and prostate cancers (7). This is despite the substantial social, vocational, aesthetic, functional and psychosocial effects associated with head and neck cancer diagnosis, treatment and recovery (6). It is challenging to develop a standardized support group format that accounts for the diversity of group purposes, structures and desired outcomes for participants. The goals for support groups vary based on participant cohorts, support group design, outcome measures and study design: to minimise psychosocial issues (8), provide emotional support, education and information (9,10), decrease depression and anxiety (11), share the illness experience and raise public awareness and fundraising (10), advocacy, socialization and affirmation (12); and improve QOL (13,14). Longitudinal evaluation is fraught with challenges inherent in a volitional support group where membership may have a higher turnover rate due to recovery or cancer recurrence. To meet a real, rather than presumed need, support groups in cancer care address several factors: (I) responsiveness to the needs of its members (12); (II) consideration of family, friends and staff (15); (III) a focus on content that is of interest to its members (9), and (IV) consideration of an interface that best suits its community (16,17).

This study investigated the above factors to guide the design of a support group for patients with head and neck cancer and their networks at a tertiary oncology hospital in Sydney, Australia (Chris O’Brien Lifehouse). It was hypothesized that in a survey of both patients and their caregivers, the majority would prefer an in-person support group, with a smaller group interested in an online forum. In a study from the United States of America, Hu et al. 2017 found low awareness of available head and neck support groups (10%), we expected similar awareness in our cohort.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ajo-20-65) (18).

Methods

This study utilised a cross-sectional survey design. The survey was distributed to patients with a diagnosis of head and neck cancer and their caregivers between January to May 2019. All patients had been treated with curative intent at Chris O’Brien Lifehouse, Sydney. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethics approval was given by Sydney Local Health District Area Health Service, Protocol X18-0089 & LNR/18/RPAH/128 and all patients provided informed consent.

Eligible participants were adults (18 years or older) diagnosed with head and neck cancer in the last 6 years (2013–2019) who had completed treatment. Patient lists were cross-referenced with the NSW death registry. Caregivers were anyone who supported or had a close personal relationship with the patient. The survey questions and supportive topics were written after reviewing existing literature and consulting with an expert panel comprised of a Dietitian, Speech Pathologist, Head and Neck Nurse Specialist, Psych-Oncologist and Head and Neck Surgeon. Surveys were distributed in clinic waiting rooms, online and via post. Those who indicated an interest in participating but had either low literacy skills or were from a culturally or linguistically diverse background were given the option to complete the survey verbally or with an interpreter.

Preferences and opinions of the support and education required by participants were collated and assessed through use of a REDCap survey developed for this purpose. REDCap is a secure, web-based application for creating, distributing and analysing research data in health care. The survey questions are outlined in Appendix 1. Results of the surveys were analysed using descriptive statistics. A subsequent analysis was conducted using “The R Project for Statistical Computing 3.6.0” and the lme4 package modelled binomial logistic regressions with various combinations of variables, for example, years post treatment and number of treatments to determine if any variable could predict likelihood that a respondent would express interest in a support group.

Results

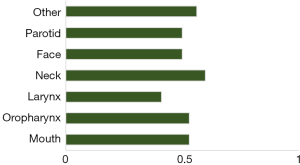

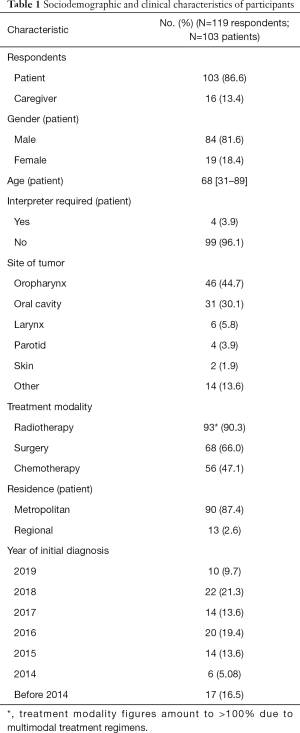

The total number of surveys distributed was 389 with 119 respondents (30.6%). There were 103 (86.6%) patients with a diagnosis of head and neck cancer and 16 (13.4%) caregivers. Of the patient cohort, four patients (3.9%) utilised an interpreter for the survey to be completed. Patient demographics, tumour site and treatment are summarised in Table 1. Figure 1 shows little variability between patients’ tumour location and their interest in a support group. There was no correlation between more treatment modalities and likelihood of indicating “yes”.

Full table

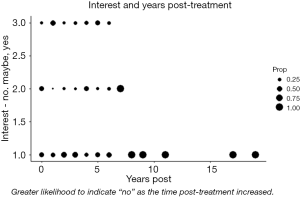

Figure 2 was constructed to show the proportion of respondent’s that answered “no”, “maybe” or “yes” given time post treatment. There appear to be no significant relationships between time post treatment and the desire for a support group.

In addition to the above graphical treatment, a number of logistic binomial regression models were run to determine if any variables had predictive power explaining the interest of respondents in a support group—none of these models returned results with significance.

Chart above was constructed to show that there is little variation between patients’ tumour locations and their interest in a support group. Values represent the average likelihood that a patient with a tumour in that location responded either “yes” or “maybe” to the question “do you have interest in a support group?”—note that some patients may fall into more than one category.

Information satisfaction

The majority (82.5%, n=85) of participants who received information at each time interval indicated that they were either satisfied or very satisfied with the information provided. Fourteen (13.6%) were neutral and 4 (3.9%) were unsatisfied or very unsatisfied.

Support group preferences

Fifty-one-point-five percent of respondents (n=53) indicated they would like to be involved in a support group for head and neck cancer, a further 26 (25.2%) were unsure, and 24 (23.3%) declined. Of those who indicated either “yes” or “I’m not sure” (N=79; 76.7%), the majority elected for a regular support group held at their treating hospital (N=55; 69.6%), with 24 (30.4%) preferring an online web-based chat forum. Of those who elected “not sure”, the majority continued to submit their responses and selected multiple topics of interest.

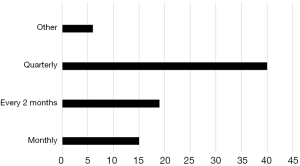

Participant preferences for frequency and timing of support groups are detailed in Figure 3 with quarterly meetings held on a weekday in the morning being the most preferred.

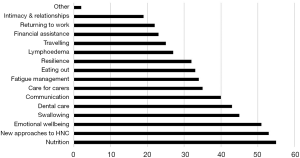

Figure 4 lists the 15 topics provided; ranked from highest to lowest interest level, the top three subjects were nutrition (53, 67.9%), new approaches and technology relating to head and neck cancer (54, 65.4%), and emotional wellbeing (48, 63.0%). Of those who indicated they were interested or “not sure” if they were interested (N=79) in a support group, the median number of topics selected was 6 (range, 1–15).

Most respondents (93.2%) were unaware of other head and neck support groups available to them. Those who were aware of other support groups were already participating in a NSW laryngectomy group, online international head and neck cancer group, or social media.

Caregiver responses closely mimicked those of the participants with the most common request for education being for emotional wellbeing and nutrition. They too were largely unaware of existing support groups.

Discussion

This study including 103 patients with head and neck cancer demonstrates that many would like to be involved in a dedicated head and neck cancer support group. The higher distribution of males compared to females was representative of what is typically seen in Australia (1). A higher number of oropharyngeal cancers in this cohort is also consistent with the rising incidence of oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) cancer on account of the HPV (19). While it was hypothesized that respondents with more complex treatments may desire more formal support, this proved not to necessarily be the case. It highlights areas of unfulfilled information and support needs and identifies the support group characteristics desired by head and neck cancer survivors. The breadth of unmet needs discovered likely reflects the diversity of QOL and functional deficits experienced by patients who have undergone head and neck cancer treatment. There were no trends identified as to the patients and caregivers who would be more interested in engaging in a support group.

The findings are similar to those reported by Jabour et al. (2017) who identified deficits in information provided to patients regarding emotional well-being, psychosexual health and practical aspects such financial assistance (16). Our study provides an outline for others to prioritise and organize their own support group, which addresses the individual care requirements of patients as they evolve over time. The respondents ranged considerably in their time following treatment completion; however, this timing did not affect interest in attending a support group. While those in the early stage of recovery are more likely to be requiring guidance around a complicated rehabilitation process, those who were diagnosed and treated over 5 years ago are more likely to be seeking support to manage the chronic nature of head and neck cancer-related side effects.

The results of this survey will inform a support group delivery model with potential to be replicated in other institutions. The first and third most frequently selected items; nutrition and emotional wellbeing are frequent complications arising from a diagnosis and treatment for head and neck cancer (20,21), affecting patients both physically and emotionally. This is consistent with Rehse and Pukrop (2003) (22) who found that a support group’s priority is the provision of emotional support and expressing a shared experience among peers. Problems swallowing, communicating and eating out were areas of unmet need and contribute to the social isolation and difficulties returning to work often experienced by head and neck cancer survivors, a challenge also raised by the respondents of a UK survey (23). These information and support needs reflect patient and their caregiver emphasis on the support of allied health professionals, particularly dietitians, speech pathologists, specialist nurses, social workers and clinical psychologists. It also highlights that support groups combining education with emotional support are most valued by participants (23,24). Preferences regarding support group delivery mode (face to face or online) are likely to be driven by several factors, dependent on participant computer literacy, geographical location, working status and personality. Many of those who declined interest in a support group specified that information and support received during treatment was sufficient and they no longer required assistance. This is encouraging for the proportion of patients who are successfully rehabilitated.

Although the sample size is small, the disparity between the low proportion of patients aware of support groups (7.8%) and those indicating their interest in one (46.2%) is of concern considering the degree of psychosocial distress and known impact on QOL. This metric may vary by sample population and whether their treating hospital has a support group. Some online resources are available that seek to connect patients and caregivers with support groups in their region (e.g., Beyond Five) (25); however, this is only helpful if such groups are available at location accessible to the individual and appropriately structured to meet the person’s needs.

The value and significance of these findings are complex. The question of whether availability of a support group has an impact on the QOL or function of its participants has been met with conflicting results. The majority of studies have found positive correlations between support groups and QOL in cancer care (10,11,13), and specifically in the head and neck cancer population (14). However, Mowry and Wang (2011) (26) and Petruson et al. (2003) (27) found no difference in QOL measures between those who did and did not attend the support group; the authors suggest reasons for lack of improved QOL measures may be related to participant’s degree of social isolation, patient selection and presence of underlying depressive disorders.

Opportunities provided by new technologies must also be evaluated. The use of telehealth and online support groups (OSG) should be examined in the process of support group planning and implementation. Studies have examined these platforms finding that an online community provided an opportunity for emotional support and stress management (17). There also exists potential for individualised, patient-centred support for clinical and emotional needs; this is of particular value to geographically diverse patients (16).

In our study, interest in a support group was high even though most respondents indicated that they were satisfied with the support and information given before, during and after their treatment. It is surmised that the satisfaction in treatment information is distinct from information required for living with long term side effects from such treatment. There is also a separate desire to meet others who have lived the same experience. The degree to which information is absorbed can be dependent on the receptibility of the patient and the context of their diagnosis and subsequent treatment; many patients experience a treatment pathway that deviates from their expectations, with considerable associated stress. For this reason, Newell et al. (2004) (28) concluded that the content and timing of information provision needs to be individualised. Absorption and application of useful information may be better suited to a post-treatment information and support group.

The results from this study indicate that a support group (face to face and/or online delivery) warrants consideration for those at varying stages of their recovery and with different cancer subsites. Should this be initiated, both Mowry and Wang (2011) (26) and Petruson et al. (2003) (27) raise the importance of considering underlying depressive disorders of participants and providing access to the appropriate management and support.

Strengths and limitations

Whether the respondent was a patient or carer, time since diagnosis, location of primary cancer and treatment modality for head and neck cancer diagnosis were examined, however factors such as ethnicity, relationship status, perceived level of support, premorbid mental and physical comorbidities and living arrangements were not ascertained or analysed. The majority of respondents were from metropolitan areas, and as such, our sample may not be representative of the information and support needs of regional residents. This, combined with voluntary participation and literacy requirements for inclusion, may mean the sample is not completely representative of the population of patients with head and neck cancer and their caregivers. Participation and non-response bias cannot be ruled out when applying these results. Specifically, those with low literacy, those who are not proficient in English, minorities and those from non-metropolitan areas may be under-represented, and those who have a particular support need, may be over-represented. While the responses were anonymous, there may have been a tendency for patients to respond in a way they felt was socially desirable and complementary to the service they were treated by, increasing the chance for acquiescence bias. It is also acknowledged that patient preferences may not correlate with improved QOL outcomes.

Relative strengths were the inclusion of both patients and caregivers, those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds and a combination of patients from metropolitan and regional areas.

Future studies

Future studies could assess whether head and neck cancer support groups are most effective at particular time points along the cancer journey (diagnosis, treatment or recovery). Comparing the needs of the patient versus caregiver, genders, age and tumour sites may also yield more targeted results. As the trajectory of diagnosis, treatment and recovery in head and neck cancer varies greatly, it may also be valuable to determine if support groups should be separated into cancer sites, aetiology or treatment modalities. A separate information and support group for those requiring palliative care may also be warranted. Pre-existing mental health conditions, anxiety and support networks should also be assessed when planning the degree of professional involvement, eligibility criteria and duration of the group.

To our knowledge this is the first study that examines the unmet information and support needs of patients who have completed treatment for head and neck cancer to inform the development and implementation of a tailored support group. The objective of the study was to establish support group interest in a cohort of patients from our facility, providing literary support to oncology care clinicians considering similar projects. The results highlight the importance of consultation with prospective participants prior to commencing a support group to ensure a real rather than a presumed need is met.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ajo-20-65

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ajo-20-65

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ajo-20-65

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ajo-20-65). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Ethics approval was given by Sydney Local Health District Area Health Service, Protocol X18-0089 & LNR/18/RPAH/128 and all patients provided informed consent.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Australia C. Head and neck cancer in Australia 2020. Available online: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/affected-cancer/cancer-types/head-neck-cancer/statistics

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:4550-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi K, Hisamatsu K, Suzui N, et al. A Review of HPV-Related Head and Neck Cancer. J Clin Med 2018;7:241. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eades M, Chasen M, Bhargava R. Rehabilitation: long-term physical and functional changes following treatment. Semin Oncol Nurs 2009;25:222-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ziegler L, Newell R, Stafford N, et al. A literature review of head and neck cancer patients information needs, experiences and views regarding decision-making. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2004;13:119-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer. A randomized outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:527-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morse KD, Gralla RJ, Petersen JA, et al. Preferences for cancer support group topics and group satisfaction among patients and caregivers. J Psychosoc Oncol 2014;32:112-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu A. Reflections: The Value of Patient Support Groups. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;156:587-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schou I, Ekeberg O, Karesen R, et al. Psychosocial intervention as a component of routine breast cancer care-who participates and does it help? Psychooncology 2008;17:716-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson J, Lane C. Role of support groups in cancer care. Support Care Cancer 1993;1:52-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vakharia KT, Ali MJ, Wang SJ. Quality-of-life impact of participation in a head and neck cancer support group. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;136:405-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammerlid E, Persson LO, Sullivan M, et al. Quality-of-life effects of psychosocial intervention in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;120:507-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heiney SP, Goon-Johnson K, Ettinger RS, et al. The effects of group therapy on siblings of pediatric oncology patients. J Assoc Pediatr Oncol Nurses 1989;6:17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright K. Social support within an on-line cancer community: an assessment of emotional support, perceptions of advantages and disadvantages, and motives for using the community from a communication perspective. J Appl Commun Res 2002;30:195-209. [Crossref]

- Jabbour J, Milross C, Sundaresan P, et al. Education and support needs in patients with head and neck cancer: A multi-institutional survey. Cancer 2017;123:1949-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Silva D, Ranasinghe W, Bandaragoda T, et al. Machine learning to support social media empowered patients in cancer care and cancer treatment decisions. PLoS One 2018;13:e0205855 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Rev Esp Salud Publica 2008;82:251-9. [PubMed]

- Aupérin A. Epidemiology of head and neck cancers: an update. Curr Opin Oncol 2020;32:178-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Bokhorst-de van der Schuer. The impact of nutritional status on the prognoses of patients with advanced head and neck cancer. Cancer 1999;86:519-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JH, Ba D, Liu G, et al. Association of Head and Neck Cancer With Mental Health Disorders in a Large Insurance Claims Database. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;145:339-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rehse B, Pukrop R. Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: meta analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies. Patient Educ Couns 2003;50:179-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Squibb BM. Beyond Clinical Outcomes UK patient experience in head and neck cancers 2019 [cited 2019 July 4, 2019]. Available online: https://www.theswallows.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/APPROVED-HN-Report-final-1.pdf

- Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW. Group therapy in the cancer setting. J Psychosom Res 1998;45:191-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Head & Neck Cancer Australia. What support is available? 2020 Available online: https://www.headandneckcancer.org.au/health-and-wellbeing/find-support

- Mowry SE, Wang MB. The influence of support groups on quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. ISRN Otolaryngol 2011;2011:250142 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petruson KM, Silander EM, Hammerlid EB. Effects of psychosocial intervention on quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2003;25:576-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Newell R, Ziegler L, Stafford N, et al. The information needs of head and neck cancer patients prior to surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2004;86:407-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Charters E, Findlay M, Clark J, White K. Support group preferences for patients with head and neck cancer: cross-sectional survey. Aust J Otolaryngol 2021;4:13.