The O.P.E.N. Survey: outreach projects in Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) in New South Wales

Introduction

Outreach clinics are an important means of providing direct face-to-face access to specialist care for those residing in remote areas. Otolaryngologists have been involved in Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) outreach clinics for many years across Australia. The coordination of such services has generally been poor. In many circumstances, towns rely on the goodwill of volunteer surgeons who journey out to remote communities to conduct clinics. A better understanding of which surgeons travel to which towns and how frequently would benefit the efficient delivery of ENT care and avoid areas being neglected.

In New South Wales (NSW), three quarters of otolaryngologists live and practice in the four main metropolitan areas of NSW (Sydney, Newcastle, Gosford and Wollongong). Outside of these areas, only about ten regional towns in NSW have access to a locally-based ENT surgeon. For rural and remote patients, outreach services overcome the huge geographic divide and many of the associated financial costs and disruptions to family, community and work commitments often incurred when accessing urban-based care.

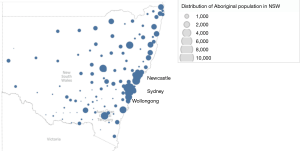

Outreach ENT services are particularly important for Australia’s Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander people (hereafter Aboriginal people). For Aboriginal people, barriers to care can include factors such as the geographic remoteness of the community, socioeconomic status and the cultural appropriateness of provided services (1). NSW has the largest Aboriginal population of any state in Australia, estimated to be 216,000 in the recent census (2). The Aboriginal population is widely distributed across NSW as seen in Figure 1, with 55% living outside of the major cities (4).

Aboriginal people also experience a disproportionate burden of ENT-related conditions, most notably middle ear disease, but also head and neck cancer (5). Aboriginal children experience higher rates of chronic tympanic membrane perforation and chronic suppurative otitis media with prevalence of the latter in the range of 10.5–30.3% (6). These conditions require timely review by an ENT surgeon to avoid long-term hearing impairment and its consequent impact on speech and language development and educational attainment (7).

Previous health workforce surveys suggest Australian ENT surgeons have relatively high rates of outreach participation relative to colleagues from other specialties. National cross-sectional studies in 1997 and 2014 reported participation rates of 29% (8) and 33% respectively (9). Both studies indicated continuity of care was high with many surgeons providing long-term care.

The current study examined in more depth the situation in NSW, focusing on where and how frequently outreach programs run in order to map the coverage across the state. Secondary outcomes included analysis of which bodies have funded these projects and also insights into what proportion of surgeons, not currently involved in outreach, might be interested in pursuing this in the future. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ajo.2019.04.01).

Methods

The O.P.E.N Survey (Outreach Projects in ENT in NSW) was conducted between December 2016 and May 2017 using an 11-question survey administered online or over the phone.

Study design was completed with the consultation of ENT surgeons, Aboriginal medical practitioners, Allied Health professionals and public health academics and approved by the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Committee (AHMRC) Ethics Committee (174/16).

Survey period

Five-year period: January 1st 2012 to December 31st 2016.

Inclusion criteria for study cohort

- Current practicing member of the Australian Society for Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery (ASOHNS);

- Primary place of practice (as recorded in the ASOHNS membership directory) in NSW or ACT.

Exclusion criteria for study cohort

Responses from retired surgeons or ENT surgical trainees.

The O.P.E.N. Survey (Table 1)

Table 1

| Question | Response options (where applicable) |

|---|---|

| In which year did you become a member of the Fellowship of Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (FRACS) in Otolaryngology? | – |

| In which state is your primary place of practice? | ACT; NSW; QLD; VIC; TAS; NT; WA; SA |

| Since January 1, 2012 have you been involved in at least one ENT outreach clinic in Australia but outside of NSW? | Yes; no |

| Since January 1, 2012 have you been involved in at least one ENT outreach clinic in rural or remote NSW? | Yes; no |

| Over the past 5 years, on average, how many full days of outreach ENT clinical work have you conducted per year in NSW? | – |

| When did your most recent outreach clinic in NSW take place? | In the last 3 months; in last 6 months; in the last year; in last 5 years; prior to 2012 |

| Which of the following government or non-government organisations provides the majority of financial support for your outreach ENT clinical work in NSW? | Rural Doctors’ Network (RDN); Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS); Local Health District (LHD); Primary Health Network (PHN); Rotary Australia; The Poche Centre; self-funded; philanthropic individual or organisation; other |

| List the names of the NSW towns in which you have conducted ENT clinics since January 2012. | – |

| For each of the towns you listed what is the main source of financial support for your outreach work? | – |

| Would you like to conduct ENT outreach clinical work in Australia over the next 5 years (2017–2021)? | Yes; no |

| Do you have any general comments regarding outreach ENT service delivery? | – |

ENT, Ear, Nose and Throat.

The survey was conducted in two stages. A hyperlink to an online questionnaire was distributed to all active NSW/ACT members of ASOHNS via 3 emails over a 3-month period (December 2016 to February 2017). In May 2017, structured telephone calls were made to survey non-responders by 1 of 3 study investigators (G Shein, AJ Saxby and S Tobin). Telephone correspondence adhered to the same questions as found on the online questionnaire. Survey responses were collected and managed using the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) online platform.

For the purposes of the study, an “outreach service” was defined as an ENT service delivered outside of an ENT surgeon’s contracted hospital commitments with NSW Health, ACT Health or other private healthcare providers. Responses were reviewed by three study investigators (AJ Saxby, G Shein and K Gwynne) and consensus reached regarding whether a surgeon’s reported activities constituted an “outreach service”.

Continuity of care was analysed by considering “surgeon-town relationships”, defined as one specific surgeon’s connection to a specific town, enabling evaluation of duration of any given relationship. A surgeon-town relationship might be one visit or continue for 5 years.

Responding surgeons were categorized according to the year of their fellowship conferral and grouped into 3 periods “Before 1990”, “1990–2004” and “After 2004” to compare differing levels of professional seniority.

The relative remoteness and socioeconomic status of each town were assessed using the Australian Standard Geographical Classification—Remoteness Area Category (10) and Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage decile (11) respectively.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft® Excel® Version 12.0 (California, 2008) and SPSS version 25 for Mac (Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

The survey was sent to 141 ENTs, of whom 86 responded (30 in online format and 56 by telephone call), giving an overall response rate of 61.0%.

Surgeon involvement

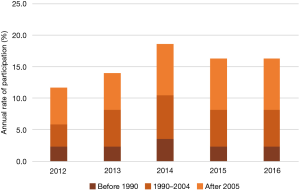

Between January 1 2012 and December 31 2016, 18 surgeons conducted at least one ENT outreach service in NSW. However, in any given year, the rate of participation was lower, averaging 13 surgeons (15%), as seen in Figure 2. A total of 498 days of clinical outreach were provided over the 5 years. Younger fellows (FRACS achieved post 2005) represented the largest subgroup, with nine surgeons responsible for 283 outreach days.

Locations of outreach

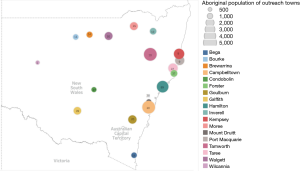

Outreach ENT services were provided in 18 distinct towns in NSW over the 5-year period. A mean of 5.5 days (SD 4.2 days) of outreach ENT services per year was provided to each of these towns. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the towns visited and the extent of outreach ENT service received. In terms of geographic location, three towns were located in “Major cities” of NSW, six were in “Inner regional” locations, five were “Outer regional” and three were delivered in “Remote” NSW and one was delivered in a “Very remote” area within NSW. All outreach services occurred in towns with an Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage that fell within the lowest five deciles. The total days of outreach received by each town from 2012 to 2016 and the size of its Aboriginal population is represented in Figure 3.

Table 2

| Town | Degree of rurality | Index of socioeconomic disadvantage (decile) | Surgeons providing outreach (n) | Total days outreach received, 2012–2016 (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bega | Outer regional | 4 | 2 | 54 |

| Bourke | Remote | 2 | 1 | 11 |

| Brewarrina | Remote | 1 | 2 | 14 |

| Campbelltown | Major city | 3 | 1 | 30 |

| Condobolin | Outer regional | 2 | 2 | 27 |

| Forster | Inner regional | 2 | 4 | 36.5 |

| Goulburn | Inner regional | 3 | 1 | 20 |

| Griffith | Outer regional | 4 | 2 | 39 |

| Hamilton | Major city | 4 | 4 | 89 |

| Inverell | Outer regional | 2 | 3 | 9.5 |

| Kempsey | Inner regional | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Moree | Outer regional | 2 | 5 | 35 |

| Mount Druitt | Major city | 1 | 1 | 38 |

| Port Macquarie | Inner regional | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| Tamworth | Inner regional | 4 | 3 | 9.5 |

| Taree | Inner regional | 2 | 4 | 36.5 |

| Walgett | Remote | 1 | 1 | 30 |

| Wilcannia | Very remote | 1 | 1 | 1 |

ENT, Ear, Nose and Throat.

Continuity of care

There were 39 distinct surgeon-town relationships over the 5 years, of which 31 were maintained for 2 years and 24 were maintained for at least 3 years. As Figure 4 shows, 11 towns received visits by more than one surgeon over the study period, with Moree receiving outreach services from five surgeons; the most of any town. The number of locations to which a given surgeon provided outreach ranged from 1 to 6, but the majority of surgeons visited just one location. Fifteen respondents involved in outreach work reported their last outreach activity occurred within the last 12 months.

Funding

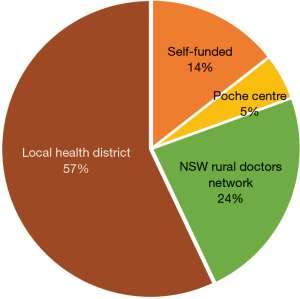

The funders of surgeons’ reported outreach ENT services in NSW is shown in Figure 5. A total 284 days were funded by the Local Health District (LHD), representing 57% of outreach days delivered. The NSW Rural Doctors Network (RDN) and the University of Sydney Poche Centre for Indigenous Health (Poche Centre) funded a further 117 days (23.5%) and 25 days (5%) respectively. Seventy-two days of outreach services (14.5%) were self-funded.

The future of ENT outreach

A total of 51 surgeons (62.2%) were interested in providing an ENT outreach service over the next 5 years. Sixteen of these surgeons have been involved in outreach ENT service delivery between 2012 and 2016, whilst twice that number (n=35) who expressed interest have not been involved to date (Table 3). Only two surgeons currently involved in ENT outreach did not intend to continue their participation.

Table 3

| Year awarded FRACS | Yes (n) | Total yes (n) | Total yes (% of cohort) | Possibly (n) | Potential pool of outreach surgeons (n) | No (n) | Total respondents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Currently providing outreach (n) | No current outreach (n) | |||||||

| Before 1990 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 42.1 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 19 |

| 1990–2014 | 5 | 9 | 14 | 56.0 | 2 | 16 | 9 | 25 |

| After 2005 | 9 | 20 | 29 | 76.3 | 0 | 29 | 9 | 38 |

| Total | 16 | 35 | 51 | 62.2 | 3 | 54 | 28 | 82 |

ENT, Ear, Nose and Throat; FRACS, Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.

Surgeons who obtained their FRACS after 2005 recorded the highest rates of interest in future outreach work, 76.3% (n=29). By comparison, 56.0% (n=14) and 42.1% (n=8) of surgeons who were awarded FRACS between 1990 and 2004 and before 1990 respectively were interested in future outreach work.

Female surgeons reported a proportionately higher rate of interest in future outreach participation of 71.4% (10/14 respondents), compared with 60.3% of their male colleagues (41/68).

Discussion

Outreach ENT services improve equity in access to this specialised care for Australians residing in rural and remote areas. They play a particularly important role in addressing the inequity in access to ENT care for Aboriginal people (12). Aboriginal children experience a higher prevalence of otitis media (13), middle ear disease-related complications (14) and hospitalisation for ear disease. This burden of ear disease is greatest amongst Aboriginal people living in remote Australia (15) who, are also least able to access metropolitan-based ENT care and therefore most likely to benefit from an outreach service.

Specific data on the precise ENT needs of rural and remote communities in NSW and the extent to which they can be addressed through outreach services is not available. However, national data on access to consultations by ENT specialists suggest the needs of the NSW’s Aboriginal population are not being met by current services. The Darwin Guidelines for management of otitis media recommend ENT specialist assessment within 6 months of referral by the primary care physician (16). In a survey of Aboriginal Medical Service General Practitioners in rural and urban practices, Gunasekera et al. found waiting times to see an ENT specialist exceeded 6 months in about 1 in 7 cases (14%). Similar unmet needs exist when considering access to ENT surgeries for Aboriginal people in NSW (17). Despite experiencing a much higher prevalence of otitis media, Aboriginal children in NSW experience lower rates of surgical treatment for this condition compared with their non-Aboriginal peers. This is mainly due to “differences in socioeconomic status and geographical remoteness” with rates of surgery lowest among children living in a remote community (18). Improved outreach services to deliver consultations and operations is therefore one important way in which these unmet assessments and surgical problems could be addressed.

Our survey found just 18 independent locations for outreach services, suggesting outreach coverage is sparse at best. Among these locations the remote and very remote towns (Bourke, Brewarrina, Moree, Walgettt and Wilcannia) are most reliant on outreach services to overcome the barriers of accessing metropolitan-based ENT care. Given the socioeconomic disadvantage (shown in Table 2) and relatively high burden of Aboriginal ear disease that exists in these remote towns there is, in fact, a need for higher than average levels of ENT services. We found, however, that these rural and remote towns appear to receive far less than their equitable share of ENT services. Across NSW there exists approximately one ENT surgeon per 50,000 population (19). Considering the example of Bourke, its population of 2,867 should ideally afford it about 69 days of outreach over a 5-year period, assuming all ENT services are equitably distributed across the state and ENT surgeons work 240 days per year. We found it received only 11 days of ENT outreach over this period, representing just 16.0% of this ideal standard. Similarly, the remote and very remote towns of Walgett, Moree, Brewarrina and Wilcannia all received far fewer days of outreach than would be equitable, ranging from 6.9–33.0% of the ideal standard. While some of the shortfall may be overcome by patients travelling to metropolitan centres it is unlikely to compensate for the degree of underservicing. Follow-up research will examine the extent to which patients from these areas are able to access outreach or permanent ENT services in larger towns. Linking outreach provision to the current and predicted population distribution would facilitate improved accessibility across the state.

The importance of regular and reliable outreach service delivery to communities is well-established. Several definitions of sustainability in the context of outreach medical specialist service delivery have been proposed (1) each of which emphasizes the importance of services being delivered on a regular basis, integrated with local services and supported by stable funding sources. It is reassuring to note that the study found approximately two-thirds of surgeon-town relationships spanned at least 3 years. This is significant as regular follow-up visits may positively impact on success rates of ENT procedures performed remotely (20).

Our study found that over half of the towns in receipt of outreach services were visited by more than one ENT surgeon over the 5-year period. Whilst assisting in the prevention of gaps in service provision, this can also lead to poor continuity of care. Building trust in the community with a regular surgeon, who shows regular commitment, is crucial for the success of the clinic and likely to lead to better participation and engagement.

Outreach specialist service delivery, including ENT services, has been a long-standing feature of healthcare in Australia. This was facilitated in 2000 by the introduction of a national health policy of subsidising specialist outreach activities. At present Commonwealth Government funds ENT services in NSW through the Department of Health’s Rural Health Outreach Fund and its NSW-based fund-holders NSW Health and the Rural Doctors’ Network. The recently-established “Health Ears—Better Hearing Better Listening Program” also provides funding for certain ENT outreach activities. Outreach service delivery is also indirectly facilitated by the “Indigenous Ear and Eye Surgical Program” which support a range of activities that overcome barriers to surgical care. However, a significant proportion of outreach remains self-funded by ENT surgeons or philanthropic donation. While such altruism is commendable, it may lead to lower rates of sustained service delivery over the longer term. Greater efforts must be made to ensure surgeons interested in outreach work are connected with available funding sources and are prepared to make a long-term commitment to communities.

Overall, we found approximately one in five ENT surgeons from NSW and ACT have conducted outreach ENT activities in the last 5 years. This translates to a yearly commitment of approximately 5 days per surgeon, equating to an average of just under 100 outreach days per year. The enthusiasm for outreach evident in both younger fellows and more established surgeons must be drawn upon, creating more opportunities for all to become involved.

Charting of proportional outreach involvement over the last 5 years (Figure 1) shows a fairly steady rate of involvement at around 15%. It is reassuring that this rate is not decreasing, but translation of intentional involvement into actual outreach participation is critical to the success of future programs. Comments expressed within the survey regarding barriers to future involvement included: lack of awareness of how to get involved; lack of organization or coordination of clinics; lack of resources for establishing new clinics; poor patient participation; time constraints and family commitments; and funding concerns for time and travel involved.

A more unified approach to outreach care across the state and country could help address some of these concerns. While this survey focuses predominantly on fly-in fly-out services, these must be integrated with wheel-and-spoke and telehealth models of service delivery.

Compulsory outreach engagement during the training stage of ENT specialization could be another key step in improving knowledge of the extent of the problem, and exposure to the way such clinics can be successful in promoting ear health in rural communities and the benefits, fulfilment and enjoyment that come from working in rural and remote communities. Hopefully, this would lead to an increased engagement in outreach services throughout their careers.

Limitations of our study

Surveys of this nature rely on accurate reporting of involvement by the surgeons involved. Retrospective recollection of such data may have inaccuracies and has not been independently verified. Despite its respectable response rate of over sixty per cent of ASOHNS members, the survey is likely to have underestimated the full extent of outreach services delivered in NSW. Surgeons providing outreach may have failed to complete the questionnaire or be among the few surgeons without ASOHNS membership who were not surveyed. Overall, proportional involvement may have been overestimated as non-participants are less likely to have responded.

There are also problems with top-down approach to capturing all outreach work. By sampling only NSW/ACT surgeons the survey misses data from interstate surgeons travelling across the border. For example, while not surveyed in this study South Australia and Victorian-based ENT surgeons are known to provide outreach services to towns on the western border and southern borders of NSW respectively. A bottom up approach, assessing each individual town in NSW and the outreach services it receives would be an alternative but more challenging methodology.

Conclusions

Approximately 1 in 5 surveyed NSW/ACT ENT surgeons are currently engaged in outreach ENT work. However, there is a significant pool of ENT surgeons, particularly younger surgeons, who intend to perform outreach work in the future. The skills and expertise of these surgeons must be channeled into well-coordinated and well-funded outreach programs. The delivery of outreach ENT services has, to date, often been piecemeal, ad-hoc and supply-driven. A more centrally-coordinated but needs driven approach should be considered to improve equity in access to ENT care and begin closure of the Ear Health Gap.

Acknowledgments

Vita Christie assisted with the collection of survey data and provided administrative support for this study.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ajo.2019.04.01

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ajo.2019.04.01). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Committee (AHMRC) Ethics Committee (174/16). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Informed consent was obtained.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gruen RL, Weeramanthri TS, Bailie RS. Outreach and improved access to specialist services for indigenous people in remote Australia: the requirements for sustainability. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:517-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. Australia. 2017. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/MediaRealesesByCatalogue/02D50FAA9987D6B7CA25814800087E03?OpenDocument. Accessed October 27, 2017.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimated resident Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Non-Indigenous population, States and Territories, Remoteness Areas. Australia. 2013. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3238.0.55.001June 2011?OpenDocument. Accessed April 10, 2017.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing - Counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2011 Australia. 2012. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2075.0Explanatory Notes12011?OpenDocument. Accessed April 7, 2018.

- Diaz A, Whop LJ, Valery PC, et al. Cancer outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in rural and remote areas. Aust J Rural Health 2015;23:4-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jervis-Bardy J, Sanchez L, Carney AS. Otitis media in Indigenous Australian children: review of epidemiology and risk factors. J Laryngol Otol 2014;128:S16-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams CJ, Jacobs AM. The impact of otitis media on cognitive and educational outcomes. Med J Aust 2009;191:S69-72. [PubMed]

- Australian Medical Workforce Advisory Committee. The Ear, Nose and Throat surgery workforce in Australia: supply and requirements 1997-2007. Sydney, Australia, 1997.

- O'Sullivan BG, Joyce CM, McGrail MR. Rural outreach by specialist doctors in Australia: a national cross-sectional study of supply and distribution. Hum Resour Health 2014;12:50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. The Australian Statistical Geographical Classification (ASGC) Remoteness Structure. Canberra. 2011. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1270.0.55.005?OpenDocument. Accessed July 17, 2017.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2011. Australia. 2013. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/2033.0.55.0012011?OpenDocument. Accessed July 17, 2017.

- Gruen RL, Bailie RS, Wang Z, et al. Specialist outreach to isolated and disadvantaged communities: a population-based study. Lancet 2006;368:130-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kong K, Coates HL. Natural history, definitions, risk factors and burden of otitis media. Med J Aust 2009;191:S39-43. [PubMed]

- O'Connor TE, Perry CF, Lannigan FJ. Complications of otitis media in Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. Med J Aust 2009;191:S60-4. [PubMed]

- Access Economics. The cost burden of otitis media in Australia. Access Economics; 2008.

- Darwin Otitis Guidelines Group. Recommendations for clinical care guidelines on the management of otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research, 2010.

- Gunasekera H, Morris PS, Daniels J, et al. Otitis media in Aboriginal children: the discordance between burden of illness and access to services in rural/remote and urban Australia. J Paediatr Child Health 2009;45:425-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Falster K, Randall D, Banks E, et al. Inequalities in ventilation tube insertion procedures between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in New South Wales, Australia: a data linkage study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003807. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Australian Government. Otolaryngology Factsheet. Canberra, ACT: Department of Health, 2016.

- O'Leary SJ, Triolo RD. Surgery for otitis media among Indigenous Australians. Med J Aust 2009;191:S65-8. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Shein G, Hunter K, Gwynne K, Tobin S, Kong K, Lincoln M, Jeffries TL Jr, Caswell J, Saxby AJ. The O.P.E.N. Survey: outreach projects in Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) in New South Wales. Aust J Otolaryngol 2019;2:14.